[Paper Reading] Karonte: Detecting Insecure Multi-binary Interactions in Embedded Firmware

Recently I read an interesting paper about IoT firmware analysis. Since I’m working around this area, I would like to introduce this and share interesting things about it.

The paper is done by UCSB Sec-lab and Ruoyu Wang’s group at Arizona University named <KARONTE: Detecting Insecure Multi-binary Interactions in Embedded Firmware>. They proposed a static analysis approach capable of analyzing embedded-device firmware by modeling and tracking multi-binary interactions.

This matches the features of IoT devices very well, previous works mainly deal with single binary analysis like Firmalice and BootStomp. However, the interactions between multiple components are often ignored or just analyzed from the perspective of behavior instead of code itself, like IoTFuzzer.

The high-level idea of this paper is to apply taint analysis to multiple “connected” components and try to figure out the paths which contain insecure data flow. For example, the user sends a request to the webserver through the web interface(like 192.168.0.1), the server accepts the request and summons a local binary to accomplish the task.

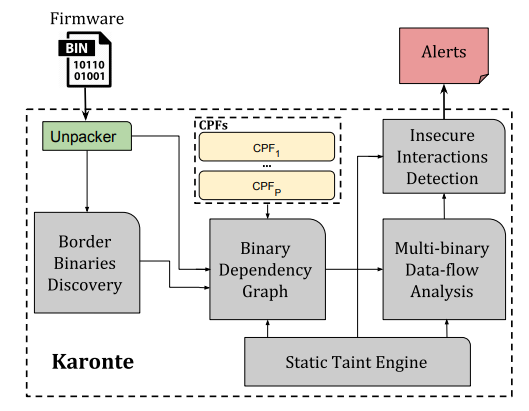

The overall structure of this approach is shown below.

Border Binaries Discovery

After successfully unpacking the firmware, Karonte’s Border Binaries Discovery module searches for “border binaries” which exports the device functionality to the outside world. Those border binaries incorporate the logic necessary to accept user requests received from external sources and represent the point where attacker-controlled data is(maybe) introduced.

The key component of Border Binaries Discovery Module is to recognize those “network-facing” binaries. The task is transformed into finding “network request parsing” functions. The authors combined metrics from previous works and proposed the following rules:

- the number of basic blocks

- the number of branches

- the number of conditional statements used in conjunction with memory comparisons

- network mark (#net)

- connection mark (#conn)

The “network mark” encodes the probability that a parsing function handles network messages. The idea is straight-forward, Karonte just locates those memory comparisons and infer the referenced string used to do the comparison. If the referenced string is in a preset list of network-encoding strings, #net increments by one.

The “connection mark” indicates if any data read from a network socket is used in a memory comparison. #conn is increased by one if there exists a data-flow between a socket read and a memory comparison operation.

Each binary has a parsing score indicating the possibility of whether it is a network-facing binary. After that, DBSCAN density-based clustering algorithm is used to get the candidates.

Binary Dependency Graph Construction

Typical taint analyses diffuse tainted data along the control flow graph to find potentially vulnerable sinks. However, in the case of multiple-binary interaction, there is no control flow graph. Karonte tackles this problem by modeling the various inter-process communication paradigms through the use of a set of modules that we call Communication Paradigm Finders.

The most common IPC paradigms used in firmware are as follows:

- Files shared by the process.

- Shared Memory. Shared memory can be either backed by a file on the file system, or be anonymous.

- Environment Variables.

- Sockets.

- Command Line Arguments.

Each instance of an IPC is identified by a unique key called data key.

Communication Paradigm Finders

CPF is used to check whether a path contains the necessary code to share data through the communication paradigm that the CPF represents. If so, it uses the following functionalities to gather them.

- Data Key Recovery. Which type of IPC the data key is of.

- Flow Direction Determination. Whether the binary is a setter or a getter.

- Binary Set magnification. Find other binaries that refer to any of the data keys previously identifies.

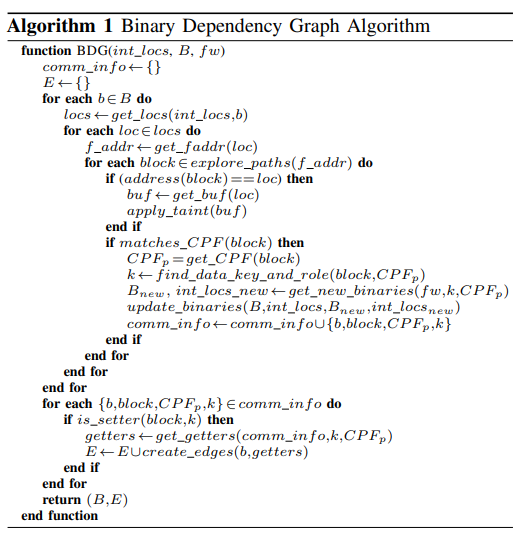

Building the BDG

Karonte models data dependencies among binaries through a disconnected cyclic diagram $G=(B,E)$. $B$ is the set of binaries and $E$ is the set of directed edges. Each directed edge is represented by a triplet $([b1, loc1, cp1], [b2, loc2, cp2], k)$ which means

the information associated with the data key k can flow from binary b1 at location loc1 via the communication paradigm cp1, to the binary b2 at location loc2 via the communication paradigm cp2.

The detailed algorithm of generating BDG is shown as the image below

To put it simply, I conclude the workflow of Karonte into following steps:

-

Use border binary discovery module to locate memory comparison locations. After that, perform a symbolic path exploration from the start of that function to the location, taint the address of the buffer used in that memory comparison.

-

After locating those sources, Karonte performs a backward taint analysis and a forward taint analysis. The taint analysis is based on angr symbolic execution engine. During the taint analyses, CPFs of Karonte check each block if the binary is sharing some tainted data, records the data key and the role(setter or getter, propagating tainted data to other binaries or receiving tainted data). By determining the roles of binaries, edges can be added to BDG.

-

Each CPF of Karonte implements a member function

discover_new_binaries, during the tainting analyses, new binaries that might communicate through the same channel (CP) will be added to the analysis queue.

Insecure Interaction Detection

The Insecure Interaction Detection module finds two types of vulnerabilities:

- memory-corruption bugs

- denial of service

For the first case, Karonte raises an alert when it finds the attacker-controlled data unsafely reaches a memcpy-like function. For the second, Karonte retrieves the conditions that control the iterations of a loop, if the conditions fully depend on attacker-controlled data, then raise an alert.

As earlier saying, buffers referenced by memory comparisons are marked as tainted data and then propagated as the symbolic execution goes on. At each step of the symbolic execution, constraints to the buffer are recorded.

Karonte refers to both memcpy-like functions and attacker-controlled loops as sinks. Once the tainted data reaches a sink during the symbolic execution, Karonte checks:

- If the sink is a loop and one of its conditions completely relies on tainted variables. An alert is raised.

- If the sink is a memcpy-like function, Karonte retrieves the address of the destination buffer and recovers its size. If the tainted buffer has a larger size (can be obtained from the collected constraints) than the destination buffer, raise an alert.

Evaluations

Authors collected firmwares from three sources – current-version Linux-based firmware(#49), Firmware Blobs from previous work BootStomp(#5) and Firmadyne dataset (#899). The authors also claim they excluded MIPS-architecture firmware samples since the incomplete support of angr for MIPS. However, according to my observation, MIPS firmware takes up the most part of IoT markets. In a total, among 8565 considered binaries, 46 zero-day CVEs are found by Karonte, indicating the approach is effective.